- cross-posted to:

- news@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- news@lemmy.world

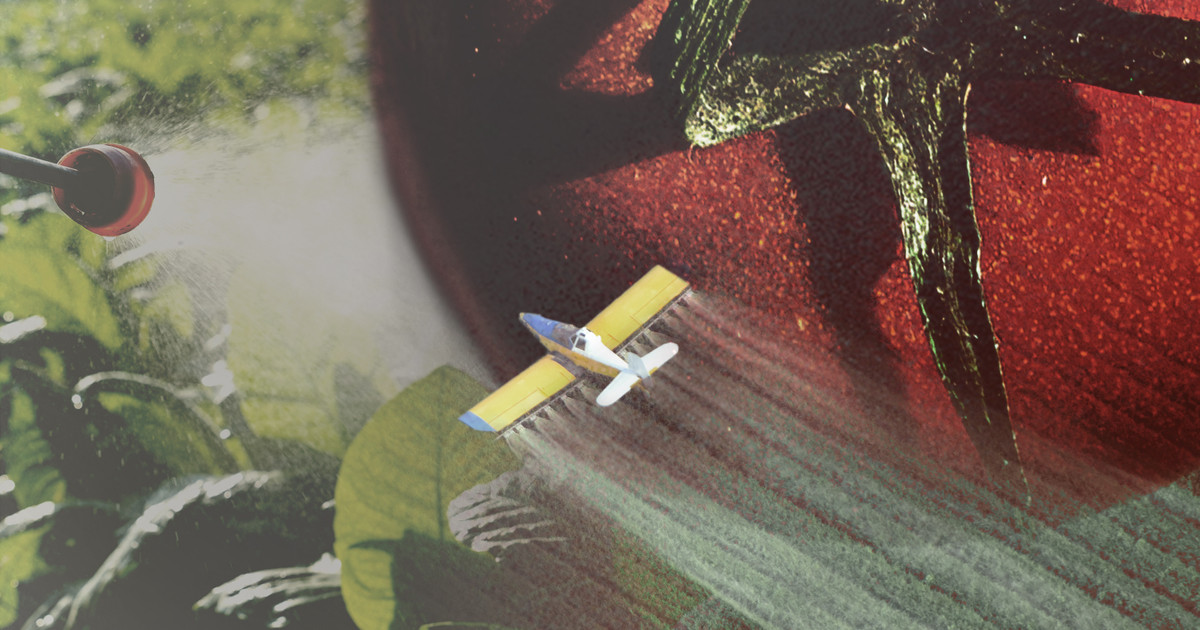

The Environmental Protection Agency unveiled a proposal this week to ban a controversial pesticide that is widely used on celery, tomatoes and other fruits and vegetables.

The EPA released its plan on Tuesday, nearly a week after a ProPublica investigation revealed the agency had laid out a justification for increasing the amount of acephate allowed on food by removing limits meant to protect children’s developing brains.

But rather than banning the pesticide, as the European Union did more than 20 years ago, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently proposed easing restrictions on acephate.

The federal agency’s assessment lays out a plan that would allow 10 times more acephate on food than is acceptable under the current limits. The proposal was based in large part on the results of a new battery of tests that are performed on disembodied cells rather than whole lab animals. After exposing groups of cells to the pesticide, the agency found “little to no evidence” that acephate and a chemical created when it breaks down in the body harm the developing brain, according to an August 2023 EPA document.

Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

EPA Proposes Ban on Pesticide Widely Used on Fruits and Vegetables

by Sharon Lerner

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

The Environmental Protection Agency unveiled a proposal this week to ban a controversial pesticide that is widely used on celery, tomatoes and other fruits and vegetables.

The EPA released its plan on Tuesday, nearly a week after a ProPublica investigation revealed the agency had laid out a justification for increasing the amount of acephate allowed on food by removing limits meant to protect children’s developing brains.

In calling for an end to all uses of the pesticide on food, the agency cited evidence that acephate harms workers who apply the chemical as well as the general public and young children, who may be exposed to the pesticide through contaminated drinking water.

Acephate, which was banned by the European Union more than 20 years ago, belongs to a class of chemicals called organophosphates. U.S. farmers have used these pesticides for decades because they efficiently kill aphids, fire ants and other pests. But what makes organophosphate pesticides good bug killers — their ability to interfere with signals sent between nerve cells — also makes them dangerous to people. Studies have linked acephate to reductions in IQ and verbal comprehension and autism with intellectual disability.

Environmental advocates, who have been pushing the agency to restrict and ban acephate for years, said they were not expecting the agency to make such a bold move.

“I’m surprised and very pleased,” said Patti Goldman, a senior attorney at Earthjustice, who has been part of a farmworker led group that expressed concerns to EPA officials over the past years about the ongoing use of acephate and other organophosphates.

As much as 12 million pounds of acephate were used on soybeans, Brussels sprouts and other crops in 2019, according to the most recent estimates from the U.S. Geological Survey. The federal agency estimates that up to 30% of celery, 35% of lettuce and 20% of cauliflower and peppers were grown with acephate.

A draft risk assessment issued in August by the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs found “little to no evidence” that acephate and a chemical created when it breaks down in the body harm the developing brain. The document said there was no justification to keep restrictions on the bug killer that are designed to protect children from developmental harm. Removing that layer of protection would allow 10 times more acephate on food than is acceptable under the current limits.

The draft risk assessment’s conclusion relied in large part on the results of a new battery of tests that are performed on disembodied cells rather than whole lab animals.

The tests have been in development for years, but the EPA’s review of acephate’s effects on the developing brain marked one of the first times the agency had recommended changing a legal safety threshold largely based on their results.

Multiple science groups, including panels the EPA created to help guide its work, had discouraged using the nonanimal tests to conclude a chemical is safe. A member of the Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee, one of the panels providing guidance to EPA, described the earlier acephate proposal as “exactly what we recommended against.”

But even as it proposed a new outcome this week, the EPA did not change its stance on the use of the cell-based tests.

“Even in this good news proposal, the EPA continues to misuse the cell-based assays,” said Jennifer Sass, a senior scientist at the environmental advocacy organization Natural Resources Defense Council.

Sass said she believes that both pressure from advocates and questions from journalists helped the EPA decide to change course on acephate. ProPublica began submitting a series of detailed inquiries to the agency about the pesticide starting in January.

An EPA spokesperson said late Tuesday that the agency had been working for months on its proposal to ban acephate from food and that neither advocates nor journalists played a role in the decision.

The EPA proposal would ban acephate on all plants with the exception of trees that do not produce fruit or nuts.

While lauding the proposed ban, Nathan Donley, a scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, expressed concern about the possibility that, after pesticide companies and agricultural groups respond to the proposal, the agency might not finalize its proposed ban. (The agency is accepting public comments through its portal until July 1.)

“The pushback on this is going to be really intense,” Donley said. “I hope they stick to their guns.”